“Let the beauty of what we love be what we do. There are hundreds of ways to kneel and kiss the ground.” –Rumi

Wind, in many ways, is like water. They’re both made of similar elements—gases of various valence—rearranged atoms to make new molecules. Wind is air. Air is mostly oxygen and nitrogen. Air heated or cooled by the earth’s surface makes wind. Water is mostly oxygen and hydrogen. Water heated or cooled propels air into wind and a perpetual embrace not unlike the yin and yang symbol of male and female; cold and hot; dark and light begins. Wind and water are sculptors of time, each utilizing its unique artistic abilities. Without hydrogen, wind must sculpt without moisture. Wind sculpts with pressure—speed and direction. Wind possesses the fluidity of water, flowing in channels and streams, with similar effect, for their purpose as creators in nature are in concordance. Their roles are based upon influence and change, a training of the land and its creatures that in turn change shape and form based upon this eternal embrace of wind and water.

Rehabilitation is a type of training. A reconditioning. A healing relief—like water falling from the sky upon the hot summer’s ground. Like wind through the stifling treetops. A sculpting—like wind and water applied to sandstone over thousands of years, creating canyons and valleys, cliffs and crevasses, gullies and lakes. And we wonder why the training and reshaping of the human condition is difficult to accomplish in a single lifetime. So much work—speed, volition, and direction. For mere flesh and blood, hardly stone. Boulders urged into precarious positions, awaiting further persuasion. Further erosion. We are like rock and stone and we must be shaped by wind and water; sun and moon; earth and sky; heaven and hell. It is the wind that I want to write about, and how it rehabilitates jagged edges, rugged stone, and makes it round and soft after a violent event—like an avalanche or a thunderstorm. The wind, that is always touching us, saying hello, face to face. Mouth to mouth. The wind that wipes our memories clean, heals us with endless possibility and whispers of what’s to come. What will always be. I think of other important “w” words that thematically apply—besides the meta example of the word “word” itself. Words like wolf, water, wilderness, wondrous, woods, walking, wayfaring, wander, worship, whimsy, wisteria, wit, winter, web, witches, wave, weather, west, weave, womb. To name a few in the most alliterate fashion. I like words that begin with “w.” “W” makes a sound that wraps you in its two arms—like feathered wings—and whispers soothing sounds. Reassuring terms and conditions. “W” is where we are at in this world, without anyone else, as one, and “w” makes our lips pucker when we pronounce it, “Wuh,”—as if we were reaching up to kiss the air, the sky, the wind. Wind and wolves and words. I wander.

It is the wind that I want to write about, and how it rehabilitates jagged edges, rugged stone, and makes it round and soft after a violent event—like an avalanche or a thunderstorm. The wind, that is always touching us, saying hello, face to face. Mouth to mouth. The wind that wipes our memories clean, heals us with endless possibility and whispers of what’s to come. What will always be. I think of other important “w” words that thematically apply—besides the meta example of the word “word” itself. Words like wolf, water, wilderness, wondrous, woods, walking, wayfaring, wander, worship, whimsy, wisteria, wit, winter, web, witches, wave, weather, west, weave, womb. To name a few in the most alliterate fashion. I like words that begin with “w.” “W” makes a sound that wraps you in its two arms—like feathered wings—and whispers soothing sounds. Reassuring terms and conditions. “W” is where we are at in this world, without anyone else, as one, and “w” makes our lips pucker when we pronounce it, “Wuh,”—as if we were reaching up to kiss the air, the sky, the wind. Wind and wolves and words. I wander.

And what causes wrinkles? Surely wind contributes, like ripples across a placid lake. And the lack of moisture. And how we age like sandstone canyons. I’ve watched Arizona canyons change with wind, water, and time—the way I watched my grandparents’ faces become etched with age, tiny wrinkles in perfection. Forged with time. With love and loss. With endurance. My grandfather was a writer and he loved the desert southwest. He managed numbers, mostly, but he loved words as well. He loved puzzles. Word puzzles. After he retired from forty years of accounting, he turned to the dozens of binders—tall shelves-full, reaching floor to ceiling in his office—to recollect notes taken on family history, etiology, naturalist notes on the desert southwest, and notes taken on his own life story. He would reshape and write a grand book with all of these notes and call it The Richard and Violet Heisey Family, by Richard Heisey, and in between firefighting seasons, I would help him edit it.

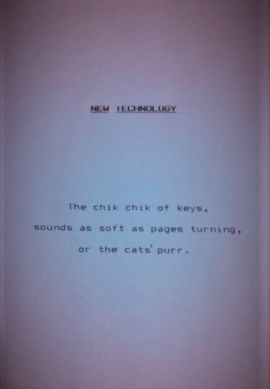

One of Grampa’s favorite forms of word puzzle was the haiku. He explained the haiku to me, once, in one of his long letters he used to write on his typewriter and mail to me—wherever I was tumbling in the wide, windy world. I knew the haiku from my studies, but not well. Grampa explained it as a simple, witty collection of words that applied to nature and revealed an unexpected result in its finale. A twist. Then he included his own unique haiku to lead by example:

New Technology

The chik chik of keys,

Sounds as soft as pages turning,

Or the cats’ purr.

I loved his haiku and I kept it safe—hand-typed on a piece of notebook paper—and found this poem, its metaphor and association of nature with words, animals with innovation, sound with substance, to be an enduring source of inspiration.

Before my Grandfather passed away, a few years after he gave me his haiku, I was fighting fires in southern Arizona and visiting him every week for dinner and song night at his retirement community. My grandmother had passed of Alzheimer’s five years prior (the death that prompted Grampa to write his autobiography and family history, as well as become a student mentor at a local Elementary school) so Grampa truly enjoyed our visits. One night he asked me what I planned to do next, when I was tired of bossing around boys and playing in trees. He could tell my mind was restless and my body tired from digging endless fire line.

“I don’t know,” was all I could say, shrugging my shoulders.

That night I went on a long walk in the desert, like I used to do with Grampa when I was a little girl. The stillness in the air—quiet Mesquite and Palo Verde branches—began to bristle. The middle-aged moon slipped in and out of clouds and stars winked through thick bushels of Arizona sky cotton. I thought about my many years in the wild, fighting fires and sleeping on the ground. With the earth. The sense of purpose it gave me, and the need for urgency. I worked with people, on a crew, but we worked for the wild—the trees, the soil, the fire—for animal habitat and rehabilitation of the land, but we worked long and hard hours with our bodies. We worked too hard, often without our minds.

That night I went on a long walk in the desert, like I used to do with Grampa when I was a little girl. The stillness in the air—quiet Mesquite and Palo Verde branches—began to bristle. The middle-aged moon slipped in and out of clouds and stars winked through thick bushels of Arizona sky cotton. I thought about my many years in the wild, fighting fires and sleeping on the ground. With the earth. The sense of purpose it gave me, and the need for urgency. I worked with people, on a crew, but we worked for the wild—the trees, the soil, the fire—for animal habitat and rehabilitation of the land, but we worked long and hard hours with our bodies. We worked too hard, often without our minds.

The wind picked up, swaying the branches in moon-shaped circles, and I felt a shift. Downdrafts rolled in from above like trembling vines, bursts of cool air like plant fingers reaching to penetrate my mind, absorb my entire being and purpose. They tangled with my hair and I’d never felt more clear. More connected to a passage. A purpose. I faced the wind, letting it spill past me, pushing tears from the corners of my hazel—green, blue, yellow, terrestrial—eyes.

I knew the sky would open with rain after the first crack of thunder. After the first note was struck in the major key of omnipotent tempests everywhere. The chorus of keys that unite storms, chaos, construction, desecration, sacrament, worship, starvation, indulgence, momentum, and power. The rain would pour out like a tincture into an open wound, flushing it clean. Striking a balance of bacterium, leaving nothing but hope and optimism and healing and opportunity in its wake. It was dark in the desert but the smell of rain and plant—creosote and dirt—let me know exactly where I was, soothing my dysphoria like salve. I was on my childhood street, where sandy washes weaved across paved roads and coyotes roamed freely. And I was walking with my best companion—wolfdog Shooter—by my side. We’d taken on so much in the back country, the front country could be no match. I was afraid of nothing. Excited for everything.

The wind blew hard in my face, distilling my mind, clearing my head, and I knew. I wanted to work with animals. I wanted to write about animals. I wanted to write about the earth and its stories. Our relationship and unique role in it all. The spark that exists between humanity and wilderness. The benevolent wildfire ignited with meaningful relationship between the two worlds that overlap like hands folded in prayer—like water and wind. I had so many stories to share and energy to give in the name of rehabilitation—for both wild and domestic realms. For wild and domestic beings. I needed to do it.

The rain began, as I knew it would, after the first roll of thunder. We took the unknown future and sporadic lightning in stride, throughout the night, and I began to make invisible plans that would emerge as flesh and fur and ink. When I got home, I wrote my own haiku. My first haiku. It went like this:

Natural History

Raindrops fall like words,

Onto a desert canvas,

Wind whispers the story.

That was my last summer fighting fires. I needed less shaping through wind and water, I was becoming the canyon—whittled by velocity, exposure, and time. I needed words. I needed thought. I needed this new form of rehabilitating nature. Shaped by the wild—molded by elements, ardor, vigor, sincere and unexpected beauty—I began rescuing wolf dogs. The first wolf dog I rescued only made sense to name Haiku.

Wow, wondrous woman of words! This is just beautiful. Glad that you are back.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So beautiful and soulful; thank you for sharing your gifts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love how you twined this together. Very inspirational.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very well written, impassioned, and emotional.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such gorgeous writing Bri!! Thank you for sharing your heart!!!❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

wow!! 1The Wind, Haiku, & Grandfather

LikeLike